Susceptibility

Magnetic susceptibility (\(\kappa\)) quantifies the magnetization (\(\vec M\)) a rock or mineral experiences when it is subjected to an applied magnetic field (\(\vec H\)). This relationship takes the form:

Magnetization

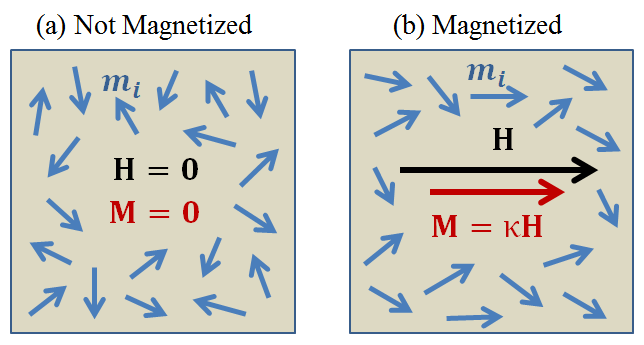

Within the mineral grains comprising rocks, there are tiny magnetized volumes (magnetic domains) which behave like small bar magnets. The direction and magnitude of each magnetic domain is defined by its magnetic dipole moment (\(\vec m\)). Magnetization (\(\vec M\)) is defined as the dipole moment per unit volume within a material.

Let \(\vec m_i\) be the magnetic dipole moment of the \(i^\textrm{th}\) particle or magnetic domain. Within a volume (\(V\)), the total magnetic moment is the sum of all individual magnetic moments, thus:

And since magnetization is the dipole moment per unit volume:

where the units for magnetization are Am \(\! ^2\)/m \(\! ^3\) = A/m.

Magnetic Field

The magnetic field \(\vec H\) is responsible for applying a magnetic force to a material. Magnetic dipoles subjected to magnetic fields will attempt to align in the direction of \(\vec H\). The magnetization process is illustrated in the following interactive figure.

When there is no external magnetic field, individual magnetic moments \(\vec m_i\) within a volume are generally disordered and hence don’t produce a net magnetic field. However, when the material is subjected to an external magnetic field, \(\vec H\), the magnetic moments try to re-orient themselves along the direction of the field. This results in a net magnetization which produces a secondary magnetic field. The following interactive figure illustrates this process:

For many materials, the strength of the alignment of the magnetic moments increases linearly with the strength of the applied field. The magnetic susceptibility therefore defines a constant of proportionality.

Magnetic Permeability

In magnetic problems, a more fundamental physical property is the magnetic permeability (\(\mu\)). Magnetic permeability relates the magnetic field (\(\vec H\)) to the magnetic flux density (\(\vec B\)). This constitutive relationship is written as follows:

The magnetic flux density depends on the magnetization within the material and can be written as:

where \(\mu_0 = 4\pi \times 10^{-7}\) H/m is the permeability of free- space. The permeability of free-space represents the relationship between \(\vec B\) and \(\vec H\) when the material is non-magnetic. For materials in which \(\vec M = \kappa \vec H\), the magnetic permeability can be defined in terms of the magnetic susceptibility as follows:

Relative Permeability

Relative permeability (\(\mu_r\)) defines the ratio between the magnetic permeability of the material and the permeability of free-space:

According to the above definitions, both magnetic susceptibility and magnetic permeability are diagnostic physical properties associated with the magnetic characteristics of materials. In the literature, it is common to see physical property tables which use \(\mu\), \(\mu_r\), or \(\kappa\). For most rocks, the susceptibility is small and charcterizing the magnetic properties in terms of \(\kappa\) is convenient. Parameters used to define magnetic properties and their associated units are tabulated below.

Property |

Symbol |

Units |

|---|---|---|

Magnetic Field Intensity |

\(\vec H\) |

A/m |

Magnetic Flux Density |

\(\vec B\) |

T |

Magnetization |

\(\vec M\) |

A/m |

Magnetic Susceptibility |

\(\kappa\) |

Unitless |

Magnetic Permeability |

\(\mu\) |

H/m |

Relative Permeability |

\(\mu_r\) |

Unitless |

Some useful conversions for units are:

The above units (with the exception of gamma) are all SI units; which can always be expressed using meters, kilograms, and seconds. Historically, units of cgs (centimeter, grams, seconds) were used to define the magnetic susceptibilities for rocks. Although it is unitless, the value of susceptibility is different when given in cgs as opposed to SI. The translation between cgs and SI units is:

The SI system is the current preferred standard among most geophysicists, but you will find cgs used in older references and texts. This can cause great confusion so be careful!

Susceptibility Measurements

KT-10 Magnetic Susceptibility Meter

The KT-10 magnetic susceptibility meter is a widely used tool for measuring magnetic susceptibilities in the field. Within the KT-10, there is an electrical circuit which produces a magnetic field. When held next to a rock, the magnetic field causes a magnetization within the rock. This magnetization changes the resonance frequency of the current within the circuit. Therefore, the KT-10 measures a change in resonance frequency, and uses it to approximate the susceptibility of the rock.

Laboratory Measurements

Laboratory measurements are based on the same physical principles as the KT-10. However, the circuit and sample holder used in laboratory measurements are more sophisticated, resulting in more accurate susceptibility values.

Susceptibility of Common Rocks

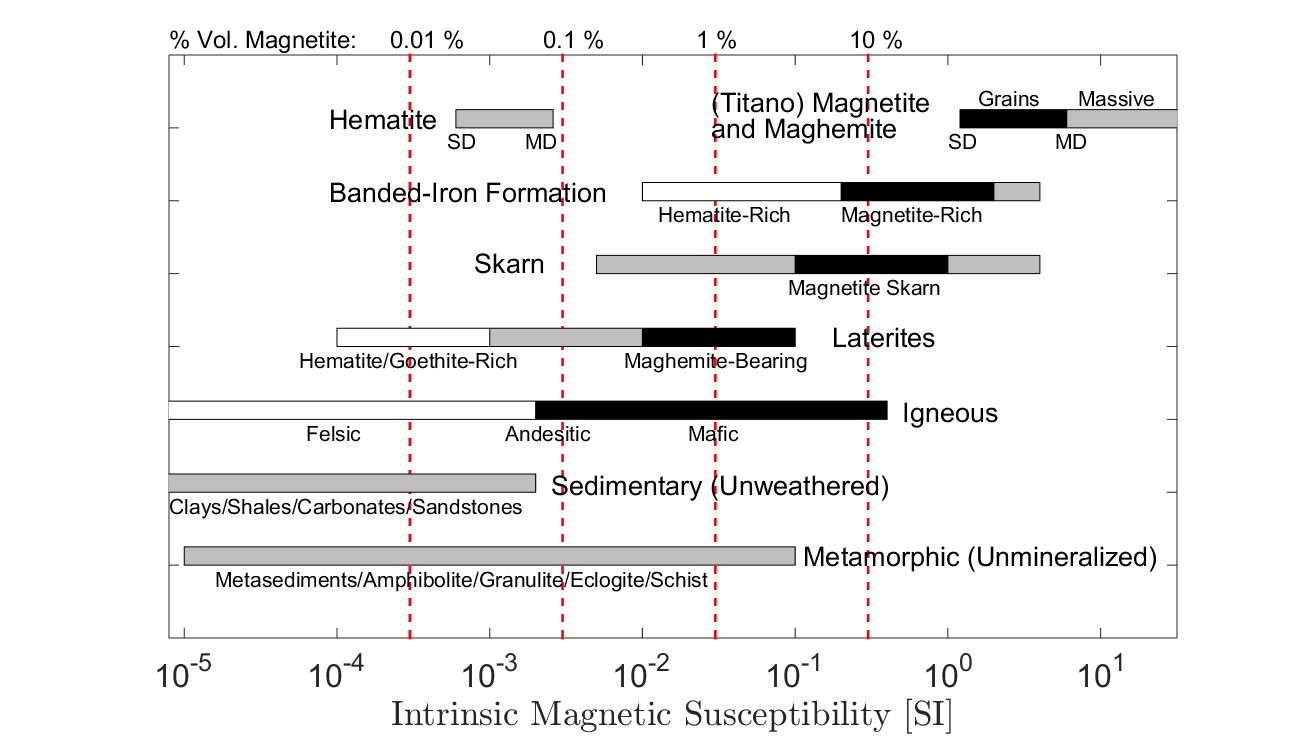

Charts showing the range of magnetic susceptibility values for common rock types are shown below. Note that the scale is logarithmic, indicating a large variability in magnetic susceptibility among rocks. From these charts we can infer several things:

Rocks with a high magnetite content are by far the most susceptible (see red vertical red lines denoting % magnetite content).

Although hematite and magnetite are both iron-oxide minerals, only magnetite is particularly susceptible.

Igneous and metamorphic rocks tend to be more susceptible than sedimentary rocks. However, there is a very wide range of overlap.

Mafic igneous rocks are more susceptible than felsic igneous rocks.

Mineralized rocks such as skarns and banded-iron formations are generally more susceptible than the surrounding country rock.

A more detailed analysis of rock magnetic properties can be found in Clark and Emerson (1991).

Factors Impacting Magnetic Susceptibility

Magnetic Minerals

The magnetic susceptibility of a rock depends on the type and abundance of magnetic minerals it contains. Magnetic minerals are generally part of the iron-titanium-oxide or iron-sulphide mineral groups. The most important magnetic mineral in rock magnetism is magnetite. This mineral is common in igneous and metamorphic rocks, and is present at least in trace amounts in most sediments. Ore-bearing sulphides are frequently susceptible due to minerals such as pyrite and pyrrhotite. The magnetic susceptibilities of notable magnetic minerals are shown below.

Mineral |

Chemical formula |

Average susceptibility (SI) |

|---|---|---|

Magnetite |

\(Fe_3 O_4\) |

5.8 |

Ilmenite |

\(FeTiO_3\) |

1.8 |

Hematite |

\(Fe_2O_3\) |

\(6.5 \times 10^{-3}\) |

Maghemite |

\(Fe_2O_3\) |

5.8 |

Pyrite |

\(FeS_2\) |

\(1.5 \times 10^{-3}\) |

Pyrrhotite |

\(Fe_{1-x}S(Fe_7S_8)\) |

1.5 |