Geotechnical example

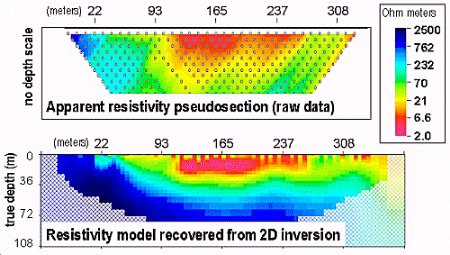

Geotechnical work also requires quantitative, accurately located information about the subsurface. Figure 7a. below shows the initial unprocessed results of a DC electrical survey over calcine tailings at the Sullivan Mine in southern BC. Lateral locations of conductive material can be interpreted directly. However, for this application, there was a need to characterize the extent and depth of the calcined material (which has a higher electrical conductivity than host rocks) partly to determine the quantity of calcine and partly to constrain the possible subsurface paths along which groundwater could travel.

Limitations of standard data presentation

The standard form of presentation shown in the top panel of figure 7, known as a pseudosection, distorts the actual distribution of subsurface physical properties. Note that no vertical axis scale is provided. Without formal inversion there is no way to identify the position and value of electrically conductive or resistive materials that gave rise to the observed data.

Also, with resistivity surveys it is important to estimate the depth of investigation because the ability to resolve geology at depth depends upon survey geometry and subsurface conductivity as well as the current source power. Traditionally (prior to development of formal inversion techniques), geophysicists used ad-hoc rules to identify the depths at which interpretations became unreliable.

Fig. 4 Figure 7: a. (top) Raw DC resistivity data from a survey over calcine tailings are plotted in pseudosection format. Resistivity values are apparent rather than true intrinsic resistivities, and the pattern is determined by the plotting convention. Circles indicate plotting points for recorded data values. The lateral surface distribution of highly conductive (i.e. low resistivity) calcine is recognizable, but details of the thickness and geometry of the conductive zone are obscured. b. (bottom) The conductivity model recovered by 2D inversion of data in the top panel. Each rectangular cell has the value of it’s conductivity determined by the inversion algorithm. The location and volume of high-conductivity material is clearly defined. The variability at the surface is due to a thin resistive cover of coarse bouldery fill overlying the area. Portions of the 2D model that are not sensitive to the survey are hatched out. Note that conductivity (which has units of Seimens per meter) is the inverse of resistivity (quoted in units of Ohm-m).

Depth of investigation

A geophysical survey provides information about a limited volume of the earth. Models produced by inversion usually extend beyond those limits. The value of a physical parameter outside the area of illumination is determined only by parameters in the inversion and does not present reliable information. To prevent over-interpretation of the inversion results, it is best to remove those regions from the final images that are to be displayed. The hatching in Figure 7b accomplishes this goal. It is evident that the geophysical survey provides no information beyond the ends of the survey line, and also the survey’s instrument geometry and source energy power results in a limited penetration depth. The maximum depth depends upon the greatest separation of the current and potential electrodes and also upon the level of signal strength compared to noise.

Discussion

There is a well-defined region of high electrical conductivity (i.e., low resistivity, in red colours) near the surface and a region of lower conductivity (blues) that appears at the surface. The low conductivity coincides with a known bedrock outcrop and this adds confidence about the interpretability of the image.

Interpretation of a precise depth for the interface between the conductive material and bedrock would be greatly aided by a single borehole drilled to a depth of roughly 50 meters anywhere within the high conductivity region. This would also help to identify the value of conductivity at which the physical interface should be interpreted.